There’s a common joke within science fiction circles derived from a Tweet by author Alex Blechman (2021). It reads, “Sci-Fi Author: In my book I invented the Torment Nexus as a cautionary tale. Tech Company: At long last, we have created the Torment Nexus from classic sci-fi novel Don’t Create The Torment Nexus”. The joke, of course, is that tech executives fail to engage with the critical aspect of science fiction—even when it’s staring them in the face. As prolific tech critic and author Cory Doctorow (2024) puts it, “Cyberpunk was a warning, not a suggestion. Please, I beg you, stop building the fucking torment nexus”.

Many of Silicon Valley’s founders do not seem to have got the message. When Meta (formerly Facebook) CEO Mark Zuckerberg made Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash (1992) required reading for his product managers, it’s unlikely that he intended to provoke reflection on the risks of corporate dominance (Freedman, 2025). It was to help them better conceptualise VR and AR technologies. This was reportedly the case for the Google Earth and Xbox teams too. The instrumentalisation of science fiction smoothes over its rough edges to produce easily-commodified blueprints. Often, the dystopian characteristics of texts are overlooked.

But the cyberpunk dystopias that have inspired a wave of metaverse products and companies are just that—dystopias. The power wielded by corporations and organised crime in the cyberpunk novels of William Gibson and Stephenson leads to worlds that are defined by inequality and violence. In Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984), it’s possible to live your entire life in the shadow of a corporation; “Company housing, company hymn, company funeral” (p. 51). And Snow Crash’s gig-economy-esque Deliveranators rush to deliver pizza within 30 minutes or suffer the wrath of Sicilian mafioso Uncle Enzo.

Subsequent works like Ernest Cline’s nostalgia-fueled Ready Player One (2011) and Norah Nagi’s “Unicorn2512” (2024) echo these same conventions. Precarious workers live in high-density sprawls or company towns; in Nagi’s story, “homes had turned into metre-by-metre rooms” (p. 118). The metaverse arises as an imperfect refuge from a cruel world. People jack in to escape. Often, this escapism is rooted in a libertarian vision of freedom by which individuals can operate beyond democratic checks and balances. It’s what game designer and academic Ian Bogost (2021) describes as “a fantasy of power”.

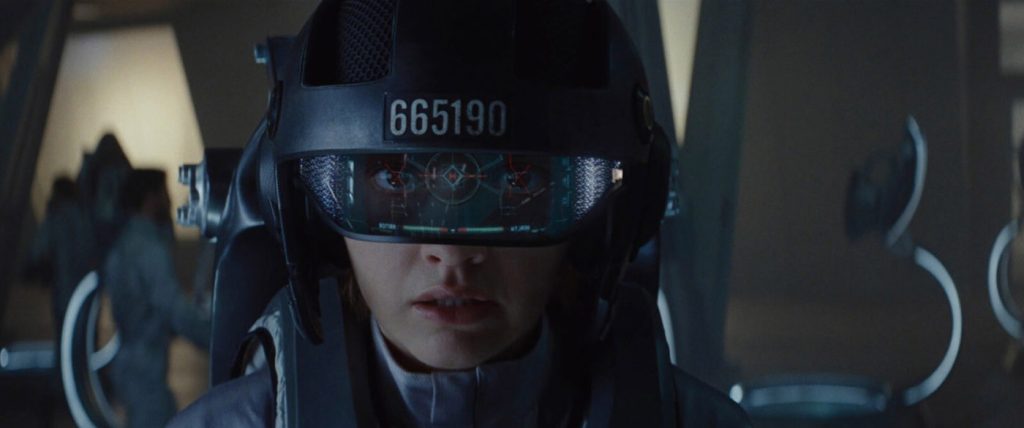

However, power is rarely distributed evenly and the metaverse is no exception. These virtual worlds are still entangled with the kinds of corporations that rule over cyberpunk dystopias; their resources and advanced technology give them significant influence within cyberspace. In Ready Player One, ownership of the virtual OASIS is offered to whoever finds an Easter egg upon the death of its creator James Halliday. This leads Innovative Online Industries (IOI) to recruit professional players called “Sixers” to hunt it in the hope that they will be able to exploit the OASIS for profit via fees and ads.

In the real world, the metaverse is being built from the ground up by companies not dissimilar from IOI. Facebook spent the past two decades influencing its users and monetizing their attention—there is no reason that its move into the metaverse will be any different. Indeed, Bogost suggests that “If realized, the metaverse would become the ultimate company town, a megascale Amazon” (Bogost, 2021). This is the case in oddball-comedy series Upload (2020): users transfer their consciousnesses to virtual environments that a corporation called Horizen owns and operates. The process is lethal for their physical bodies.

The metaverse as it exists today is a constellation of interrelated technologies shaping virtual environments and experiences. Google DeepMind’s Genie 3 model reportedly generates “dynamic worlds that you can navigate in real time” (Fruchter and Parker-Holder, 2025). Epic Games’ Fortnite is a self-styled virtual world in which players can immerse themselves in the endless dopamine churn of daily challenges, seasonal content, and the acquisition of “V-Bucks”. AI-generated NPCs are already here. Tokens minted on the blockchain present new opportunities for “ownership”. Meta’s Ray-Ban branded sunglasses blend AR and AI tech to capture data through microphones and cameras, continually surveilling users’ environments while whispering sweet nothings in their ears.

In their way, some contemporary manifestations of the metaverse are already dystopian. If their worst excesses were intensified, they could produce an inescapable “Torment Nexus” akin to the endlessly watchable “Entertainment” of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (1996). Presented with immersive environments, dopamine-hacking reward systems, and unprecedented personalisation, some may be incapable of looking away. From smartphone addiction to the obsessive use of Large Language Models as stand-ins for friends or therapists, we’re already seeing trends in this direction.

There are still limitations to these technologies, however. Announced at Meta Connect 2025, the Ray-Ban Meta Display’s live demo featured not one but two failures; the first saw Zuckerberg repeatedly fail to answer a call; the second saw the glasses ignore a question from a food influencer—“what do I do first?”—insisting they had already “combined the base ingredients”. Zuckerberg blamed the WiFi. Even if people prove willing to accept AR wearables’ constant surveillance, which wasn’t the case with Google Glass a decade ago, it seems there are issues to iron out.

The reality is that the current technology is still a long way away from the kind of immersion described in novels like Neuromancer, Snow Crash, and Ready Player One. One of the primary selling points of Meta’s Quest headsets, as well as the Apple Vision Pro, is Mixed Reality (MR) functionality. Rather than fully immersing yourself in a virtual world, you can surround yourself with application windows, play games, and stream video on a large display, superimposed on your surroundings by the headset. “Play Xbox bigger than ever on an 8-metre (26-foot) virtual screen”, Meta (2025) suggests. This isn’t the metaverse of science fiction—it’s a way of getting around the fact you, an adult, live in a small room in an expensive flatshare without the space or money for a large television.

This technology isn’t especially immersive. Often experiences that simulate motion, especially driving games, are actively nauseating. But it’s better than the drab reality many are confronted with in a world of stagnant wages and rising cost of living. It’s sub-par escapism for those experiencing a sub-par way of living—cyberpunk with the knobs turned down. Who knows? We may one day end up with a world that matches the corporate dominance and inequality that’s commonplace in cyberpunk without an accompanying metaverse that’s worth its salt.

For the moment, attention has shifted to the all-encompassing GenAI bubble. A glance at Google Trends analysis reveals that global interest in the metaverse peaked in January 2022 and has declined ever since—down from a peak 100 interest score to just 5 at the time of writing. Platforms like Fortnite have more staying power, but excitement around the concept has waned. Meta has already lost the best part of $70 billion on its VR development (Richter, 2025). Despite gains in market share, it’s hard to justify the losses of its Reality Labs Division; it’s telling that the company focused squarely on its Ray-Bans wearables, rather than Quest headsets at Meta Connect.

This is the reality of tech billionaires uncritically mobilizing science fiction’s cultural cachet to drive hype and investment. The products themselves never live up to the standards set by fictional futures, while the companies creating them exacerbate social issues and harm the environment in pursuit of record profits. It’s easy to forget that these virtual worlds are underpinned by resource-intensive infrastructure. The data centers that power cloud-based VR and AI models put considerable strain on regional water supplies. The IEA (2025) expects that their consumption will reach 1,200 billion litres per year in 2030, while building in water-deprived areas is projected by SourceMaterial (2025) to grow by 63%.

The visions that Silicon Valley produces with the help of science fiction are often ephemeral—insubstantial pageants that fade as attention shifts to the next shiny technology. But, although they don’t match the science-fictional intensity of the Torment Nexus, their harms can be very real.

References

Blechman, A. (2021, November 8). Sci-Fi Author: In my book I invented the Torment Nexus as a cautionary tale [Post]. X. https://x.com/AlexBlechman/status/1457842724128833538

Bogost, I. (2021, October). “The metaverse is bad”. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2021/10/facebook-metaverse-name-change/620449

CD Projekt RED (2020). Cyberpunk 2077.

Cline, E. (2011). Ready Player One. Ballantine Books.

Daniels, G. (Creator). (2020–2025). Upload [TV series]. Amazon Studios.

Doctorow, C. (2024, May 17). “You were promised a jetpack by liars”. Pluralistic. https://pluralistic.net/2024/05/17/fake-it-until-you-dont-make-it/#twenty-one-seconds

Freedman, S. (2025, April 14). “The big idea: will sci-fi end up destroying the world?”. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/apr/14/the-big-idea-will-sci-fi-end-up-destroying-the-world

Fruchter, S. & Parker-Holder, J. (2025, August 5). “Genie 3: A new frontier for world models”. Google DeepMind. https://deepmind.google/discover/blog/genie-3-a-new-frontier-for-world-models

Gibson, W. (1984/1995). Neuromancer. Voyager.

Meta (n.d.). This is Meta Quest. Retrieved August 30, 2025, from https://www.meta.com/gb/quest/?srsltid=AfmBOoo2LGPOmOUpJmtSDpEekCWR40swoPqPveMXIYzkKOJXKFD5Btek

Nagi, N (2024). “Unicorn2512” In A. Naji (Ed.), Egypt+100: Stories from a century after Tahrir (111–122). Comma Press.

Richter, F. (2025, January 30). “Meta’s Money Pit: Metaverse Bet Bleeds Billions”. Statista https://www.statista.com/chart/29236/operating-loss-of-metas-reality-labs-division

Stephenson, N. (1992/2011). Snow Crash. Penguin.

Wallace, D. F. (1996). Infinite Jest. Little, Brown and Company.